I remember the dream.

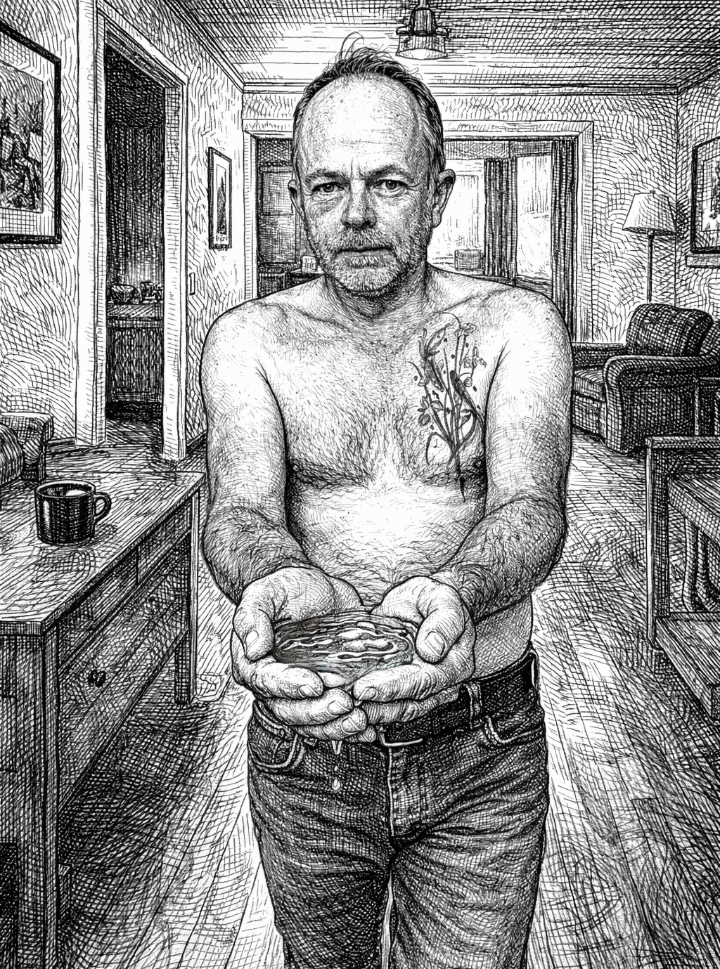

The water won't stay in my hands. I curve my palms to hold it, I walk carefully across the room toward her, but by the time I arrive there is only dampness and she is looking at me, waiting, and I have nothing to give her but wet hands and the memory of what I was carrying.

This is what it means to love in English when your heart speaks French.

I wanted to tell her something yesterday. No, not yesterday. Tuesday. Or weeks ago. I am still wanting to tell her. The days blur when you live in translation. I wanted to tell her that her presence, just her being there in the room, made the world habitable. Not liveable. Habitable. In French the word carries weight, it means worthy of being dwelt in, deserving of human presence, and I could feel this word in my body, in my chest, this precise thing I wanted to say.

Your presence makes the world more liveable, I said.

She smiled. She said thank you. And I stood there knowing that what had arrived was not what I had sent. Somewhere in the crossing, between my chest and my mouth, between French and English, the thing itself had changed shape. What I felt was architecture. What emerged was a pleasantry.

I have been here before. I am always here. Standing with wet hands, trying to explain that I was carrying something, that it mattered, that it was real even though you cannot see it now.

In my mind I am writing to her in French. Always in French. Long letters that explain everything, that find exactly the right words, that would make her understand. Je ressens quelque chose de profond et je ne sais pas pourquoi. I feel something deep and I don't know why. The translation is wrong already. Ressentir is not feel. Profond is not deep. The French version lives in my body. The English version lives in my head.

I lie in bed composing perfect sentences. I know exactly what I mean to say. In French it is clear, precise, it has the right weight and the right distance and the right music. Then I try to put it into English and watch it become something else. The meaning slides away like water through fingers.

She tells me I make assumptions. She tells me I move too fast. Things feel like pressure when they should feel natural. She is right. What she cannot know is that these assumptions, this speed, they are my clumsy attempts to bridge a gap she cannot see. I cannot find the words in English to say what I mean, so I paint pictures of what I imagine we could be. I cannot express the specific quality of how I feel, so I describe futures, possibilities, outcomes. To her this looks like racing ahead. To me it feels like drowning.

The gap between us is not what she thinks it is.

My mother tongue. They call it this because you learned it from your mother, but also because it mothers you. It holds you. It allows you to be small and uncertain and still articulate. French is my mother tongue and English is my stepmother. Competent, professional, functional. It does not love me the way French loves me. It does not let me rest.

I remember trying to tell her something about an exhibition. I had been walking through rooms of paintings and I kept thinking of her. My chest hurt. I wished she were there. Her absence was a kind of violence against the experience itself. The paintings needed her eyes. I needed her eyes on the paintings so I could see them properly.

I sent her a message: I thought of you today at the exhibition.

But in my head, in French, what I meant was: your particular way of seeing makes the world visible to me in ways it is not visible when you are absent, and standing in front of these paintings I felt your absence as a physical thing, as if the space next to me had a weight and a shape, and I wanted you there not as an accessory to my experience but as the necessary condition of the experience itself.

She read: I thought of you today.

The water was in my hands. By the time it reached her it was gone.

There are words in French that have no equivalent. Disponibilité. Being available, yes, but more than this. Being emotionally present in a way that creates space for the other person. Being there in your attention, in your consciousness, in the quality of your listening. I wanted to tell her that this is what I felt from her, that this is what I wanted to give her, but there is no word for this in English and so I said I want to spend time with you and she heard something ordinary when I meant something essential.

The philosopher said the limits of my language are the limits of my world. He did not say what happens when you live in two languages and neither one can hold what you need to say. You fall between them. You live in the gap. Your world has no limits because it has no ground.

I think of Wittgenstein often now. I think of him in English, which means I think of him incompletely. In French I would think of him differently. The thoughts would have different shapes, would arrive at different conclusions. But I am thinking in English because I am trying to understand why I cannot make myself understood in English. This is the trap, this is the violence. I am using the language that fails me to understand why it fails me.

She said I made her feel small. This is the thing I cannot forgive myself for. My attempts to be seen made her feel unseen. My struggle to express depth came across as assumption. My vulnerability, which in French would have registered as openness, landed in English as pressure.

I have been thinking about this for weeks. Months. Time is strange when you are stuck in one moment, turning it over, trying to find the angle that makes it make sense.

In French, when you tell someone that you feel something deep, something you cannot quite name, this is an invitation. It says: I am confused by my own feelings and I want to explore them with you. Vulnerable without being demanding. It acknowledges uncertainty while asserting experience. In English this same statement sounds like certainty. Like I have already decided what this is and I am asking you to catch up.

The same words. Different languages. Different worlds.

I wanted to tell her that I carry her with me. That she occupies space in my consciousness even when she is not there. That thinking of her is not a choice I make but something that happens to me, like weather, like seasons. In French this is romantic. In English this is intense. The feeling is the same. The reception is opposite.

Sometimes I wonder if this is why I left France. I needed to learn what it means to be inarticulate. To know what it feels like when words fail. In France I was eloquent. I could say what I meant. I could be understood. Maybe this was too easy. Maybe I needed to learn what it means to reach and not arrive.

But this is just a story I tell myself to make the loss meaningful.

The truth is simpler. I came here and I fell in love and I could not make myself understood and she went away and I am still here with my two languages, neither of which can hold what I need them to hold.

At night I write her letters in French. Long letters. Letters that explain everything. Letters that find exactly the right distance between intensity and reserve, between honesty and respect, between what I feel and what can be received. These letters are perfect. They say exactly what I mean. They would make everything clear.

I do not send them because she does not read French.

Instead I write to her in English and the sentences are never right. The tone wrong, the rhythm wrong, everything slightly off like a photograph that is almost in focus but not quite.

She will remember me as someone intense, difficult, who moved too fast and made assumptions. I will remember her as someone I could not reach no matter how hard I tried. Both things are true. Both things are incomplete. Neither of us will know what actually happened between us because it happened in the space between languages and that space has no words in either tongue.

The truth is we were speaking different languages and neither of us knew it. She thought we were speaking English. I thought I was speaking English. But I was speaking French badly translated into English and she was hearing English inflected with expectations I did not know I was carrying.

The water in my hands. The dampness on my palms. The look on her face when I arrived with nothing.

I understand now that some things cannot be translated. The words exist but words are the wrong unit of measurement. You cannot translate a feeling. You cannot translate a culture. You cannot translate the specific way that French shapes thought and English shapes thought and the two shadings are so subtle that you do not even notice them until you try to love someone and realise you are speaking past each other in what sounds like the same language.

This is not about her anymore. She was just the place where the problem became visible. The problem being that I live between languages and therefore I live between worlds and therefore I live between selves and none of these selves can quite reach the others.

The French self, the self that can say what it means. The English self, competent and professional and slightly wooden. And between them, the self that exists only in translation, only in approximation, only in the gap between what is felt and what can be said.

I am the water and the hands and the space between. I am the meaning that was lost and the meaning that arrived and the unbridgeable distance between the two.

She is gone now. What I loved was the possibility of being understood. What I lost was the illusion that translation is possible.

I do not know anymore. The knowing happens in French and the not knowing happens in English and I live between them, in the space where nothing is certain and everything hurts and the words keep failing and I keep trying anyway because what else is there to do.

I remember the dream.

The water won't stay in my hands.

(to M.)