We Left France. That's Why We Can See It Clearly.

I recently published an article comparing Emmanuel Macron's 1,350-word New Year address with Anthony Albanese's 200-word statement. The piece analysed what that gap reveals about institutional health in France versus Australia.

Philippe Gaudron, former president of UNIDIS whom I worked in close collaboration with when I hold the CEO position, commented: "More expats should make French elites realise their vanity and incapacity to operate change, evolution, development. Open your eyes, open your mind."

This rings a bell. We worked together navigating the very institutional systems I now analyse from distance. His observation captures something essential, especially as we approach the 2026 elections for Conseillers des Français de l'étranger.

Let me be clear about my position. I'm not angry at France. I'm frustrated for France. That distinction matters.

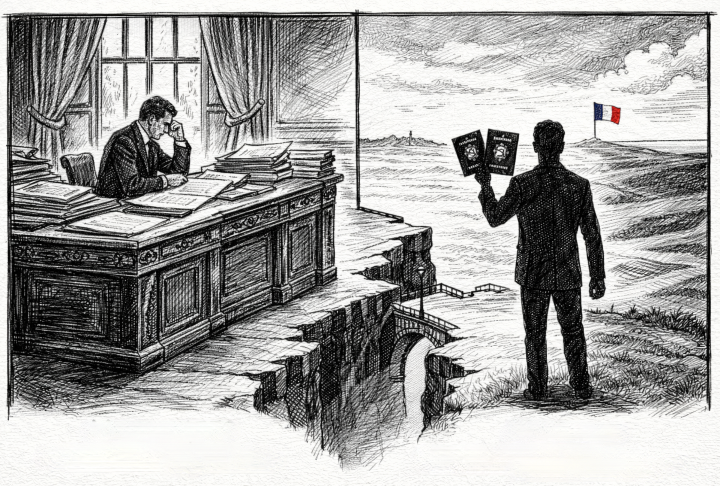

I didn't leave as rejection. I left as choice, choosing institutional competence over cultural prestige, systems that function over systems that theorise about functioning. Australian citizenship wasn't about stopping being French. It was about refusing to pretend French institutions still worked when my daily experience proved otherwise.

This isn't bitterness. This is diagnosis. And France needs diagnosis more than cheerleading.

The Exodus and What It Reveals

2.5 million French citizens live abroad, though the real number likely exceeds official estimates since consular registration remains optional. I'm among the 42 per cent holding dual citizenship, part of the 58 per cent with higher education who left not for lifestyle but because building anything meaningful in France had become nearly impossible.

The 2025 Gallup data tells a stark story. Twenty-seven per cent of French people now consider permanent emigration. The desire to leave has more than doubled in a single year, reaching an all-time high in nearly two decades of tracking.

Young professionals cite the reasons plainly: lack of opportunities, excessive tax burden, toxic atmosphere. One restaurant entrepreneur who relocated from Paris to Tbilisi told Euronews: "There's a lot of hatred between people. People prefer to pull at each other rather than help each other." An engineer still in Paris explained he couldn't buy a home in his birth city despite a management career. "Without an inheritance, I couldn't live in the town where I was born."

France has become an emigration country. Demographer Hervé Le Bras observed that France worries endlessly about being "submerged by immigrants" while becoming a source country "without creating the resources and statistical tools to grasp the causes." French elites won't study why people leave because examining the question might require acknowledging the answers.

I can write comparative institutional analysis precisely because I've lived both realities. I tested French institutions by building organisations there, sitting on national boards, navigating the system from inside. I was directly involved in social and workplace reforms, involved in politics at the local level, aiming to balance my national role with my local role as a citizen implicated in a small village 50 kilometres south of Paris. Then I tested Australian institutions by succeeding here, building a life, becoming a citizen. The comparison isn't theoretical. It's lived experience.

This is the binational advantage. Research shows dual nationals feel just as French as those who renounced their original nationality. Eighty-two per cent in both groups. The difference isn't loyalty. It's perspective.

What you see from that vantage point disturbs. French exceptionalism doesn't match reality. Institutions don't deliver their promises. The gap between French self-image and international perception has become unbridgeable. Worse, French elites have no mechanism to acknowledge this because their entire position depends on maintaining the illusion.

Macron speaks for 1,350 words because France's systems demand constant explanation. Albanese speaks for 200 because Australia's don't. That gap reveals everything about institutional health versus institutional theatre.

Elite Reproduction and Institutional Sclerosis

I recently came across an old Guardian article referencing Peter Gumbel's 2013 book examining France's elite education system. His conclusion still resonates: "France is badly served by its elites. They are brilliant at writing reports, but much less skilled at putting the conclusions into practice."

More recent French scholarship confirms this analysis. Sociologist Camille Peugny has documented France's declining social mobility in "Le Destin au berceau," showing how background increasingly determines outcomes despite meritocratic rhetoric. His research advocates for structural reforms inspired by Scandinavian models that successfully combine social mobility with economic competitiveness, precisely the kind of comparative institutional analysis French elites systematically ignore.

Julia Cagé's work on democratic institutions and Thomas Piketty's recent research on institutional capture both demonstrate how French administrative elites reproduce themselves through the grandes écoles system, creating networks that control political, economic, and administrative institutions simultaneously. Their empirical research confirms what expats observe from outside: French elite reproduction isn't accidental. It's structural.

The mistrust between French people and their elites dates to 1789. Thirteen major political changes since the Revolution produced remarkably little change in who actually governs. ENA and Sciences Po create a closed circulation where the same kinds of people from the same schools occupy the same positions generation after generation.

Companies with these old-boy networks perform relatively poorly. In public sector, French elites missed most important developments of the past two decades in improving government efficiency and transparency. They excel at conceptualising problems and fail at solving them.

This matters for expat voices because we threaten that comfortable system. We've seen alternatives work. We can point to Australian federal-state coordination and say, "This actually functions." We watch parliaments pass budgets without Article 49.3 and constitutional crisis. We've experienced civil service continuity rather than obstruction.

French elites dismiss these observations by questioning our loyalty. "You left, so you don't understand current reality." But that's backwards. We left because we understood French reality better than those who stayed comfortable within it. We tested whether other systems worked better. They do.

Young French professionals cite deterioration of human relations, lack of confidence in juniors, discrimination based on origin. These aren't abstract complaints. They're diagnostic observations from people who know what healthier systems feel like.

Seventy per cent of talented young French believe France is in decline. Eighty-one per cent worry about the political situation. Seventy-four per cent about the economic situation. These aren't pessimists. They're realists watching a country that refuses to acknowledge its problems.

France has more founders of unicorn companies in the United States than in France itself. Forty-six in the US versus around 22 in France as of 2024. Not because French people can't build valuable companies. Because the French system makes it unnecessarily difficult while other systems make it comparatively easy.

French elites are brilliant at diagnosing problems. They write comprehensive analyses of what needs to change. Then they do nothing because implementing change would threaten the system that gives them position. Expats see this clearly because we've left the system. We're no longer invested in maintaining illusions that protect status. We can say what needs saying because we've chosen other homes where speaking plainly doesn't threaten our livelihood.

Why the 2026 Councillors Elections Matter

The question then becomes: how do expat voices actually reach French decision-makers? How do we transform individual observations into collective testimony that French elites can't simply dismiss as isolated complaint?

Last month, I decided to join Serge Thomann's list as Western Australia representative for the 2026 Councillors for French Citizens Abroad (Conseillers des Français de l'étranger) elections. Some people asked why bother. The role has limited formal power. It's largely advisory. Many French expats don't even know these elections exist.

But here's what they represent. One of the few formal mechanisms for French citizens abroad to have voice in how France engages with its diaspora. A channel through which comparative perspectives can reach decision-makers. A statement that we haven't given up on France even though we've chosen to build lives elsewhere.

The French diaspora needs stronger representation not because we want special treatment but because we have knowledge France needs. We understand how other countries solve problems France claims are insoluble. We see how other systems create opportunity where French systems create obstacles. We know from daily experience that many things French elites insist are impossible are actually just difficult.

Running for Conseiller isn't about personal ambition. It's about building infrastructure through which expat voices can be heard. It's about creating networks that connect French citizens across Australia so our comparative insights reach critical mass. It's about refusing to accept that distance from Paris means irrelevance to France's future.

Strengthening French networks abroad matters for our lives in Australia and for France itself. When French expats connect, when we share comparative insights, when we build collective voice through mechanisms like the Conseillers elections, we create pressure French elites find harder to ignore.

One expat writing an article is interesting. Ten expats sharing similar observations is a pattern. A hundred expats organised through elected representatives is a constituency. A network of thousands across Australia offering consistent comparative analysis backed by lived experience becomes evidence harder to dismiss.

The 2026 elections are small in scope but meaningful in symbolism. They say: we haven't given up. We're still engaged. We believe France can change. We're willing to work towards that change even from distance. We're offering our comparative perspectives not as criticism but as contribution.

What Binationality Means in Practice

I hold both French and Australian citizenship. I'm not torn between loyalties. I'm informed by dual perspectives. I can see what works in Australia and what doesn't in France not because I'm disloyal but because I actually care whether French institutions serve French people.

French politicians treating dual nationality as suspect loyalty miss the point entirely. We didn't leave because we stopped caring. We left because we cared enough to stop pretending dysfunction was normal. We found places where baseline institutional competence exists. Now we watch France struggle with problems that could be solved if elites would acknowledge they exist.

Taking Australian citizenship didn't make me less French. It made me bilingual in institutional realities. I can compare what Macron promises with what Albanese delivers because I've lived under both systems. That comparative knowledge threatens French elites because it reveals their excuses don't hold up.

"We can't pass budgets because parliament is fragmented." Australia passes budgets with diverse parliaments. "We can't coordinate policy because we're too centralised." Australia coordinates federal-state relations despite geographic vastness. "We can't implement reform because people resist change." Australia implements major reforms when governments explain why they're necessary.

French institutional dysfunction isn't inevitable. It's choice. Maintaining elite privileges over societal function. Defending closed systems over open opportunity. Prioritising cultural prestige over institutional performance. Expats see these choices clearly because we've experienced alternatives.

Macron's approval rating sits at 28 per cent. Sixty-seven per cent of French people believe their situation is deteriorating. France is the most economically pessimistic OECD country after Greece. Political instability, budget paralysis, rising far-right proceed while elites insist the system fundamentally works and just needs better communication.

The 2027 presidential election approaches with the same elite assumptions that produced current dysfunction. The same schools producing the same kinds of leaders proposing the same solutions that haven't worked for decades.

French expats watch from abroad with sadness and frustration. Many would return if France created conditions where building meaningful things became possible again. But return requires belief that change is possible. Everything we see suggests French elites prefer managing decline to admitting failure.

Why Expat Voices Matter Now

France's problems aren't mysterious. They're well-documented, thoroughly analysed, completely obvious to anyone who's experienced functional alternatives. The problem isn't diagnosis. It's implementation. Implementation fails because the people who would need to implement change are the same people protecting the system that needs changing.

Expat voices threaten that comfortable arrangement. We can say what needs saying without losing position because we've chosen other positions elsewhere. We can point to functioning alternatives because we live in them daily. We can insist change is possible because we've experienced it.

Not because we're disloyal but because we're free. Free from social pressures that keep people in Paris silent. Free from career calculations that make criticism dangerous. Free from the need to maintain illusions that protect status.

This freedom matters more than French elites realise. When we organise observations, when we strengthen networks that amplify our voices, when we use mechanisms like the Councillors elections to formalise our input, we transform from diaspora into resource. Not a resource to be extracted but knowledge France desperately needs.

The question for 2027 isn't who wins the presidential election. It's whether France will continue with elite assumptions that produced current dysfunction or finally acknowledge what comparative analysis reveals.

I'm not optimistic about immediate change. The same schools will produce the same leaders proposing familiar solutions. But silence implies consent. More expats should speak up, not because French elites will suddenly listen but because other French people need to hear that alternatives exist.

Twenty-seven per cent of French people consider leaving. They need to know their instincts are sound. They need permission to trust their own experience over elite rhetoric.

France's institutions don't work as promised. This isn't opinion. This is observable fact. Other countries have solved problems France claims insoluble. This isn't theory. This is comparative evidence.

You're not disloyal for noticing dysfunction. You're not pessimistic for wanting change. You're not unpatriotic for considering alternatives. You're just paying attention.

The 2026 Councillors elections are one mechanism for organising expat voices. Strengthening French networks across Australia is another. Writing articles that connect our observations is a third. Each action builds towards something larger: a diaspora that refuses dismissal, that offers perspectives France needs, that stays engaged because change remains possible.

We left France. That's why we can see it clearly. Now we need to make sure France can see what we're seeing.